Pay-for-Success for the Success of Social Innovation in Hong Kong

This article appeared originally in the Standard on 07 November,2018.

Authors:Johnson Kong, Assistant Researcher at The Public Policy Institute Of Our Hong Kong Foundation ; Kendrick Hung, Senior Consultant, Dalberg Advisors

Shortage of elderly care centers, growing prevalence of chronic diseases, worsening situation of homelessness – Hong Kong people are no stranger to these social problems. Despite the efforts made by hundreds of non-governmental organizations, these issues have remained unsolved for years. This situation could be explained by the risk aversion of bureaucracy, who rarely get along with risky innovation as long as they have to bear the full risk of it. Fortunately though, in the face of similar challenges around the world, a new instrument was invented to take the risk off government’s shoulder. Its name is Pay-for-Success (PFS).

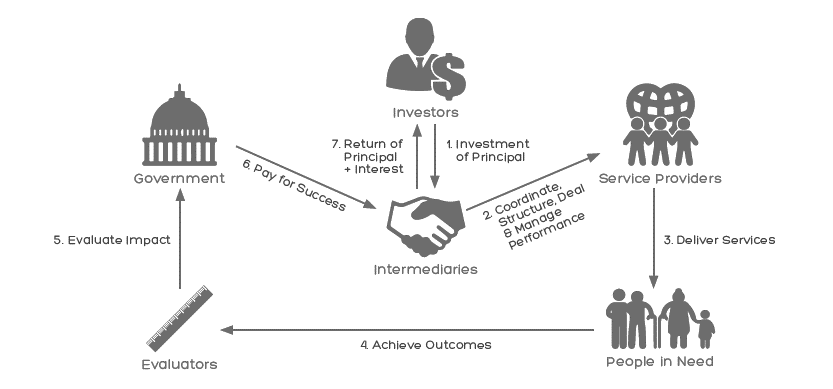

Figure 1. The Mechanism of Pay-for-Success

PFS (also known as Social Impact Bond) is a form of result-based contracting developed in the United Kingdom, first started in 2010. As illustrated in Figure 1, a social service project is financed by investors in PFS. Government will pay investors a financial return along with the principal based on the service performance, which will be assessed by independent evaluators. Via this mechanism, government need not bear the full cost of the project in case of unsatisfactory performance. Meanwhile, the risk of project failure is shifted, at least partially, to the investors. PFS is particularly advisable for preventive projects that may incur future cost savings for the government since the interest payment to investors can be covered by part of the savings.

The innovative instrument is spreading across borders. As of January 2018, there have been a total of 108 PFS projects diffusing across 25 countries and the number keeps rising. One successful example is the SIB program on chronic kidney disease in Japan.

Embroiled by the tremendous healthcare costs and growing mortality rate related to kidney disease, the Kobe City government decided to employ PFS in 2017. To finance a health guidance program comprising medical examinations and dietary modification, the Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC), Japan Social Impact Investment Foundation (SIIF) and a number of retail investors provided an upfront capital of about 30 million yen (HK$2.1 million), hoping for a fairly attractive blend of social and financial return.

The program would be evaluated by the Institute of Future Engineering, and the result would be submitted to the Kobe City government to determine the outcome payments – if over 75 percent of the patients adopt a healthier lifestyle and maintain their kidney function, the Kobe City government would repay the principal and an interest of up to 5 percent per annum to the investors. (As another example, the Newpin Social Benefit Bond in Australia has delivered a return of 13.16 percent per annum to investors for four years.) It is estimated that the program could potentially save the government up to 170 million yen (HK$12 million) in the long run.

PFS removes a major obstacle to publicly funded social innovation: the financial risk of failure. While there is nothing derogatory in saying that a government is financially conservative or risk-averse, as any accountable government shall keep a close watch on their spending and ensure an effective use of public money, the conflict between risk-averse bureaucracy and risky innovation remains a high hurdle to a dynamic, innovative, and progressive social sector. PFS offers a solution to this issue by shifting the financial risk of social innovation from government to investor. By tying redemption to outcome, a government would only pay investors in case of success, and proportionally to the degree of it. In effect, the government takes the risk of ‘wasting public money’ off its shoulder and achieves certainty in its investment in social innovation, which is expected to earn support from both inside and outside the government.

Moreover, seeking funding opportunities service providers are incentivized to explore and create new solutions for better outcomes. Complemented by data collection and analysis, they are encouraged to identify room for improvement and revamp their services consistently in search of what works effectively and efficiently. Considered a ‘deviant’ in the current subvention system, an innovative new service with great potential becomes a promising investment opportunity in PFS and could earn itself funding from investors for implementation. In a nutshell, PFS is powerful in unleashing the power of innovation.

The greatest risk in the battle against social problems is taking no risk at all. Innovation is needed at the system level as much as the service delivery level, for which an instrument that takes the risk off the government’s shoulder is essential. To this end, it is encouraging to learn that the Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Fund is already taking action to introduce PFS into Hong Kong. The government should not hesitate to launch a PFS pilot program, and in the meantime, social service providers and various stakeholders should build their own capacity and well prepare themselves for this upcoming trend of social development.